Camera Obscura

Historical Landmark May 23, 2001

|

August 23, 1987 San Francisco Examiner

IMAGE Inside the Camera Obscura by Karen Evans |

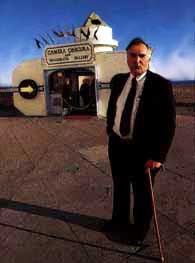

David Warren spends his days in a building shaped like a

camera out by the Cliff House. Anytime anyone gets close to his seaside

attraction, Warren pokes his head through the round window of his plastic "box

office" --housed just

to the left of the lenslike door, and asks, "Have you seen the

camera obscura?"

What they'll see, if they pay their dollar and open

themselves up to Warren's

enthusiasm, is sheer magic. They'll also get to know a man who

loves what he does.

"Take a moment to let your eyes adjust," Warren tells his

guests, once they've

walked through the swinging doors into his world. He rests his

hands on the white

rail surrounding what looks like a satellite dish, pointed

toward the sky, dominating

the small room. Swimming across that dish is a scene that looks

like a painting-- a

painting in motion.

Depending on where the camera obscura's periscope like lens

is pointed at the

moment, the view on the dish is of the walls of the Cliff House,

or of the man-made

concrete cliffs across the street, or of the condos lining the

Great Highway where

Playland at the Beach to be or of the Seal Rocks and the

Pacific. As people

watch, birds fly across the screen, a surfer rides a wave, the

sea lions stretch on the

rocks.

"The camera takes six minutes to go all the way around, but

you can stay as long

as you like, "Warren tells his guests. One man last week stayed

six hours."

At this point, Warren can put on a taped narration and go

back into his box office,

but more often than not, he stays around, just to watch the

reactions and share the

discovery. "What you are seeing is a rotating picture of what's

happening outside

at this very moment, " Warren tells his small, rapt audience.

"It works on the

principle of the periscope. It reflects eighteen degrees of the

view from outside,

through an optically flattened, front surface-finished mirror

and a series of concave

and convex lenses, on to a parabolic or curved screen.

"It was the first camera," Warren goes on to explain. "The

camera obscura was

invented by Leonardo da Vinci in the sixteenth century. His

neighbors thought it was

the instrument of the devil. They thought he could predict the

future, the past and the

present. They banned the creation because they believed it was

related to the super-

natural. That's because, "Warren continues, in his soft voice,

"people would go in

and then go out and see their friends and say, "I saw you when I

was in the camera

obscura," and people would think they'd seen the future because

they had no idea

about projected image."

David Warren, on the other hand, several centuries removed

from da Vinci's time,

has a lot of ideas about the projected image and the camera

obscura. There's very

little he can't tell you about this rare device -- how Isaac

Newton wrote about it, or

Copernicus charted the stars with it, or Renaissance artists

painted with it.

"I've been an artist all my life," he says, "and vision and

light and shadow are

wondrous things to me. Inside you become entrenched, especially

people into

the visual arts or visual optics and light.

"The vision of your eye opens up in there," Warren says.

"You see things

differently. Your optic nerve is being affected in a different

way. It stimulates

the chemical makeup and your emotions. It moves me to tears."

As the camera swings around to capture the view across the

street from the

Cliff House, Warren tells his viewers, "This is the old Playland

at the Beach.

If you are a registered voter, you can sign a petition as you go

out to put something

there other than more condominiums."

There's a reason that the former site of Playland holds a

special place in

Warren's heart. That's where he first saw the camera obscura,

when he was sixteen

years old. As a young man, Warren had show business in his

bones; he ran away

with the carnival, he learned how to eat fire.

Then Warren grew up. worked on his career as a salesman,

and lost touch with his

beloved camera. When things began to fall apart for him, he

found it again.

"I ended up separated from my family," he says. "My wife

divorced me. I

had five kids, and I went into a deep depression. How can you

sell anything at that

point?

He took up some of his old interests. He signed up for the

docent's course at the

Exploratorium and began doing research on Playland at the Beach,

Just as it was about

to be torn down. He met Gene Turtle, one of the two men who had

built the camera.

As youngsters, Turtle and Floyd Jennings had discovered

Leonardo's plans by accident,

thumbing through the Encyclopaedia Britannica for a science

project. They showed their

completed model to George Whitney, who owned the Cliff House and

Playland.

Whitney set up the camera at the Cliff House, but for the

first few years it didn't do

well because no one knew what it was. Then Whitney got the idea

to make it look

like a giant camera. Though located at the Cliff House, the

camera obscura was a

Playland attraction until they tore the place down in 1972.

Early in his career, photographer

Ansel Adams hung around the camera so much that they quit

charging him.

Warren ran into Gene Turtle in the 1970's and ended up

doing a fire-eating

demonstration at Turtle's wife's birthday party. In 1978, David

Warren was perched on

a ladder at the Balboa Theater, painting a mural on the side

-it's still there, with

Marilyn Monroe as centerpiece, but that's another story -- when

Turtle approached him

and asked whether he'd like to take over the operation of the

camera obscura.

"I told him I'd do it as soon as I got down from the

ladder," Warren recalls, "and I've

been doing it ever since."

Warren proceeded to spend years trying to figure out how to

get people in to see what

the camera had to offer. "It's a wonderful thing," he says.

"You think you should be able

to tell people what it is, But it's a paradox. As a salesman,

I knew that people would like to know about it, but I found out

that you couldn't tell them about it."

He finally hit upon a solution; tell them what it does, not

what it is. Slowly, Warren has learned the tricks of wooing

them in, has discovered where the magic line lies between those

who come in and those who wander off. A few years ago, he added

a pair of huge brass arrows, pointing to the entrance. "Before,

people would just walk by and start looking at the ocean," he

says. "Now, these get their attention."

Once the people come inside, Warren starts spilling his

enthusiasm, as the camera obscura chugs quietly around on its

motorized axis, panning the surf and the sea lions and the

sinking sun. At one point, Warren says, there were three such

cameras in San Francisco alone. Now, there are only a handful

left in the world. Dave Warren can tell you where each one is

and who if running it. That's one of his projects -- forming an

organization of all the camera obscura operators in the world,

so they can share information.

When the sun sinks low enough in the sky at the end of the

day, the sun itself is captured on the rim of Warren's

satellitedish screen, a glowing ball of concentrated light. At

that point, Warren will hold up a flat, white board, moving it

into the field of projection so that he can show people the

sunstorms around the edge of the sun.

"We always look for the sunspots," he says. "It's part of

our show. We turn off the narration tape and do the sunset show

in person. We see the green flash in here about twice a month.

It's caused by the spectrum of light being split by the

atmosphere. The various colors of light are separated. When

green comes along, it flashes, like the northern lights, just as

the last rays of light leave." Warren can't help himself; his

voice fills with awe. "It lasts only a tenth of a second, but

it's very beautiful. Liquid jade. When Jules Verne was

writing, he said if there is a green in heaven, it's surely this

green."

As people leave, Warren nearly always seems to find some

excuse to give them a free pass for another visit. ("Next time,

come back while it's still light, so you can see the sea lions"

or "Come back and bring a friend.")

The camera never fails to surprise him. "The most unusual

thing happened just the other day," says Warren. "We were

watching a sunset, and all of a sudden there was a thud. The

screen got black. I thought for sure a bird had hit the camera,

Later, when I went up to close the hatch, I reached in, and

there was a fish. A pelican probably dropped it," he says. "He

sure had good aim."

But even on more humdrum days, the object of his livelihood

and his affections totally entrances David Warren. Someday,

he'd like to create a mobile camera, on that he could haul up to

Twin Peaks. "Now that would be something," he says. Meanwhile,

if you venture down the stairs that lead to the terrace below

the Cliff House, you'll find him, polishing the brass arrows or

leaning out through the box office, trying to coax people over

that invisible line. When someone gets within earshot, Warren

is there, speaking softly. "Have you seen the camera obscura?"

|

Diving Bell | New Playland Sculptures | Camera Obscura

Sutro Photos | Cliff House | Mayor Brown's Dedication | IT's It

Herb Caen | Sunset Magazine | Playland-at-the-Beach Poster

Golden Gate Bridge 50th Party| HOME